Cleavers, Goose Grass and Sticky Willy are all common names for a rather extraordinary plant. It has a square-shaped scrambling-ascending stem with recurved hooks and its bristly seeds can frequently be found attached to your trousers or entangled in your dog’s fur after a walk in the countryside. Its adhesive properties are well known, but now researchers at the University of Lincoln have discovered another special characteristic of this common weed – it has a rather stretchy lower stem.

Galium aparine is a member of the Bedstraw family and is commonly found in gardens and in hedgerows throughout the British Isles. It is also known for its persistence as a troublesome agricultural weed; its small seeds can contaminate grain and the long stems can become entangled in combine harvesters. But cleavers also have beneficial characteristics; historically it has been boiled as spinach before the two-seeded fruits appear and in Sweden the seeds are roasted, ground and used as a substitute for coffee. The green seeds were also once used to adorn the tops of lacemakers’ pins to provide a padded head.

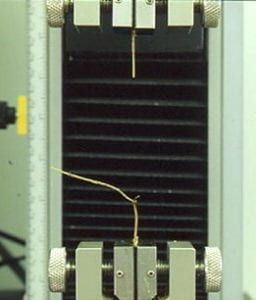

Until recently, research into this species has largely focussed on its commercial importance as an agricultural weed, but Dr Adrian Goodman, a lecturer at the University of Lincoln, has discovered that this plant has a highly extensible and relatively elastic basal stem. This can simply be observed by taking a piece of the lower stem and pulling it between your fingers. The results of mechanical tests in the laboratory showed that the lower stem stretched by up to 24 % of its original length before breaking. This is rather unusual for a terrestrial plant and it is only in aquatic species of the buttercup family and some seaweeds where similar mechanical behaviour has been observed.

So what is the mechanism behind the high extensibility? The way in which the base of the stem permits the very high breaking strains remains a mystery; the orientations of microscopic fibres in the cell walls was also measured, but there is no evidence to suggest that this is responsible for its remarkable behaviour.

So what possible function or advantage could a stretchy basal stem confer? The significance of these findings may be that the stems are better able to cope with sudden tugs, in a similar way to the stems of aquatic plants cope with changes in flow rate in their watery environment. Indeed, cleavers are commonly found scrambling up hedges and attached to upright species such as grasses; they may have evolved in such away as to minimise the effects of a support which sways in the wind. Furthermore, this species is known to be dispersed by animals; the hooked seeds are frequently found attached to the fur of animals. The stretchy basal stem may have evolved as a mechanism to help prevent the plant from being uprooted.

So when you are next weeding in your garden, walking by a hedgerow or removing the hooked seeds from your pet’s fur, pause for a moment and take time to ponder about this intriguing plant and its rather remarkable stem.

Further information (Goodman, 2005).